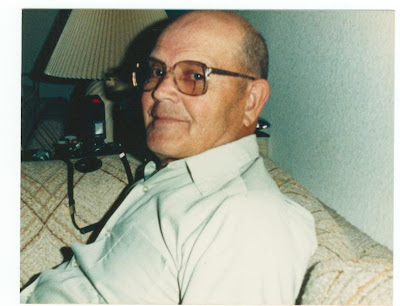

Grandpa 1983.

Grandpa with 35 lb. King Salmon.

The thin nylon cord sang as it whipped through the air to dance above shimmering green water.

I sat outside and watched him as the summer sun set in golden light behind towering Douglas firs. Deepening shadows turned the lake from emerald to forest.

Content, I sat nearby, perched on a cut-out tree round for a step, tucked into the side of a hill. Huckleberry and blackberry bushes' ripening scent hung in the warm air along with dragonflies.

We both loved the quiet at dusk, being outside, with the aroma of Grandma's cooking wafting downhill.

Grandpa worked as a mechanic at Boeing in Seattle in the 1960s and 70s. After his hour-long commute home to Monroe, he quietly walked from his home down to the lake to fly-fish.

There was a large, round piece of plywood that he'd nailed to a fallen tree where it rested in the water. He stood on it, and cast his line about 15 feet from the muddy bank.

From the age of eight through 11, I spent a month every summer with my brother Les at our grandparents' place in the woods. Most of our time was spent outside exploring or with Grandma doing errands. But it was my grandpa who fascinated me.

As I grew older, I noticed his sense of humor was subtle. He smiled at me a lot, but wasn't much of a talker.

On the way home from trips to the big city, we passed pastures of cows and horses. He tried to convince me that horses were cows and vice-versa. I pretended to agree, mooing with him at startled horses. He grinned his close-lipped smile, nodded his head, and kept driving.

In their younger days, my grandparents lived in Lake City, raising my mother and her older brother in that busy suburb of Seattle.

Later, they bought the place I remember most; a little house overlooking Lost Lake. The road was a dead end, enveloped in a wild, tangled forest of tall trees and thick bushes and deep shadows.

Their house was built on a steep slope halfway down to the lake.

Underneath the house on stilts with its wrap-around deck was a cave. When he wasn't fishing, Grandpa worked many years on that place, widening the hole to convert it into an extra living area and storage space.

To me, as I looked up at the house from the lake, it was a gaping monster mouth. For all I knew, Sasquatch lived in it. Many times I ran pell-mell up the hill to the house to avoid whatever I "knew" was hiding there. That was one place where I didn't follow Grandpa.

I knew Grandpa differently than his grandsons did. My other brothers, Marty and Jeff, visited for a month in summer as well, but my grandparents couldn't handle all four at once. Maybe it disturbed Grandpa's quiet too much.

I was the only granddaughter, and sometimes I think he didn't know what to do with me. Because he was so quiet and reserved, I didn't get to know him well at all. I was a silent watcher of him.

He taught me how to fish, and showed me around his smokehouse chockablock full of fishing rods, but that's about it. I mostly remember him fishing, or enfolded in a chair in front of a blazing fire encased in an orange, rounded pyramid-like, free-standing wood-stove while he watched television when the lake was iced over.

To remember my grandparents is to remember fish. Always fish. My grandmother was a fisherwoman.

I saved only a few black and white photos of the multitudes of trout and steelhead and salmon they caught, hung on lines by the gills throughout decades of fishing.

Even now, whenever I travel in Washington I recognize river and lake names from seeing them printed in faded black or blue ink on the backs of those photos. Skookumchuck. Skokomish. Sammamish. Toutle.

Although I never learned to fly-fish, I taught my own two children the joy of tying a hook, digging worms, the thrill of the red and white bobber popping up and down, and the adrenaline rush when the rod bent under the weight of a trout and winding it in on a taut line.

My son, Jason, walks in his great-grandfather's shadow.

He lives in Colorado, and travels to Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon with his wife, his friends, his father, and his camera. He is also a photographer of all things fly-fishing and is beginning to make a living at it.

On a visit to a crystal clear stream in the Rocky Mountains one January, Jason tried to teach me how. As always, I just loved being outdoors. Pine-scented air, the sound of frigid trickling water over smooth stones, the ziiiiing of the line as it sailed downriver were enough for me. Good thing, as I never did get the hang of it.

I think Grandpa would be proud of his great-grandson.

Jason took the elder's hobby to another level.

Yet...

I know that he knows, as Grandpa did, that there is something soul-satisfying about casting a line at the end of the day while the sun goes to rest, trout leap for flies--real or fake--and there is silence all around.

Just for fun.

Elmer Bruce Bartlett died in March 2000, age 82.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your ponderings?